As I briefly alluded to in the overview to this series, Gran Turismo 5 can be approached in three different ways: as the latest installment in the franchise, as a game that competes with other racing properties, and as a product whose development has been long and arduous. Depending on these approaches the qualities and flaws change, as does the general impression one can derive from it, making GT5 not only a complicated beast but one that deserves analysis from all angles. Today, we focus on the product side of the equation.

As I briefly alluded to in the overview to this series, Gran Turismo 5 can be approached in three different ways: as the latest installment in the franchise, as a game that competes with other racing properties, and as a product whose development has been long and arduous. Depending on these approaches the qualities and flaws change, as does the general impression one can derive from it, making GT5 not only a complicated beast but one that deserves analysis from all angles. Today, we focus on the product side of the equation.As it stands, Gran Turismo 5 is a quality title. It brings the renowned franchise into the modern-day, high-definition era with lush visuals, features that were requested for years (weather, night racing, etc.) and even 3DTV support, given Sony’s recent push in that domain. Like previous entries in the series Gran Turismo 5 is at the forefront of technology and fidelity, pushing the PS3 like no other game and standing out as a culmination, of sorts, of everything Sony wanted to achieve with their black beast. Or, so Sony would have you believe.

In reality, Gran Turismo 5, while impressive, is also quite disappointing and it’s the features I refer to above -- the very things that get mentioned when trying to demonstrate GT5’s supposed superiority over its competition -- that make it so. There’s no denying that graphically, Gran Turismo 5 is beautiful, the cars and tracks shining (literally, in some cases) like never before, demonstrating the power of the PlayStation 3. Add in the weather effects, in-car camera view and day/night transitions and you have an awe-inspiring racing game that not only shows how far we have come, but why we should have made this progress to begin with. It’s not consistent, however, and the game can be quite ugly and jarring at times, too.

A good example of the jarring graphics. This WRC car looks good... until you notice the inside of the front wheel.

A good example of the jarring graphics. This WRC car looks good... until you notice the inside of the front wheel.The obvious issue is the difference between the cars. Gran Turismo 5 has a wealth of cars that is arguably too many but respectful in the way it celebrates car engineering as I alluded to when discussing my games of 2010. Within its 1000-plus lineup exists what Polyphony call Standard and Premium vehicles. Premium cars come with all the bells and whistles, featuring immaculate replications of stunning cars such as Ferraris and Lamborghinis with meticulously detailed interiors, the ability to drive them using the in-car view, and more polygons than should be allowed for each car. There are about 200 of them, and they truly are a sight to behold. The Standard vehicles, on the other hand, are appallingly low-res and look, frankly, terrible. Their windows are tinted so interiors don’t have to be modeled; it’s impossible to drive them with the in-car view; and their shapes are nowhere near as smooth as the Premium selection, featuring jagged edges, blurry lines and a generally rough appearance. They scream Gran Turismo 4 fidelity rather than the pristine presentation of GT5, meaning that yes, they are essentially last generation cars. Considered separately the difference is irrelevant and, as a flaw, can be mostly overlooked, but every time you do an event in a Premium car and then need to switch to a Standard one, the contrast is jarring and the game jolts you back into reality, reminding you that you’re playing a videogame. Basically it’s the uncanny valley issue rearing its head again but instead of taking you out of the immersion of another game, here it just stuns you momentarily before you remember the pathetic difference between cars and resume racing. The contrast -- ugly as it is -- isn’t the problem here; instead, it stands out as inexcusable because of how long Gran Turismo 5 was in development, and because it is at such incredible odds with what the game and, indeed, the franchise has always tried to be: the pinnacle of graphical progress.

The cars aren’t the only area of the game where this discrepancy lies, however; tracks also contain jarring differences that are not only baffling, they impede on the enjoyment of the game. As gorgeous as the Madrid street circuit or the High Speed Ring are, it means nothing when tracks like the Top Gear Test Track, Laguna Seca and Circuit De La Sarthe (Le Mans) have flat, blurry textures, 2D ‘paper’ trees* and crowds with boxy heads and faces. Seeing the aforementioned Premium cars zoom around while the grass looks like it has been filled in using Microsoft Paint is not only an insult to the game’s credibility and Sony/Polyphony’s strong focus on leading the way with technology, it strongly affects enjoyment of the game seeing what feels like something from the PlayStation 2 era featuring so prominently on the PS3. When you consider that the Top Gear track in particular gets showcased on the game’s main menu screen sporadically, it’s simply inexplicable. Had Gran Turismo 5 released when it was originally supposed to way back in 2007 or even in 2008, the problem wouldn’t be as apparent and it wouldn’t be such a scar on an otherwise pleasant racing experience. Since it came out in (late) 2010 instead, after so many other racing games upped the ante and matched -- if not outclassed -- the GT franchise visually, the issue is appalling and a severe letdown to those who were expecting it to, like every other installment in the franchise before it, once again lead the way and pioneer, pushing the graphical -- not to mention photo-realistic -- limits possible in the virtual space.

The cars aren’t the only area of the game where this discrepancy lies, however; tracks also contain jarring differences that are not only baffling, they impede on the enjoyment of the game. As gorgeous as the Madrid street circuit or the High Speed Ring are, it means nothing when tracks like the Top Gear Test Track, Laguna Seca and Circuit De La Sarthe (Le Mans) have flat, blurry textures, 2D ‘paper’ trees* and crowds with boxy heads and faces. Seeing the aforementioned Premium cars zoom around while the grass looks like it has been filled in using Microsoft Paint is not only an insult to the game’s credibility and Sony/Polyphony’s strong focus on leading the way with technology, it strongly affects enjoyment of the game seeing what feels like something from the PlayStation 2 era featuring so prominently on the PS3. When you consider that the Top Gear track in particular gets showcased on the game’s main menu screen sporadically, it’s simply inexplicable. Had Gran Turismo 5 released when it was originally supposed to way back in 2007 or even in 2008, the problem wouldn’t be as apparent and it wouldn’t be such a scar on an otherwise pleasant racing experience. Since it came out in (late) 2010 instead, after so many other racing games upped the ante and matched -- if not outclassed -- the GT franchise visually, the issue is appalling and a severe letdown to those who were expecting it to, like every other installment in the franchise before it, once again lead the way and pioneer, pushing the graphical -- not to mention photo-realistic -- limits possible in the virtual space.

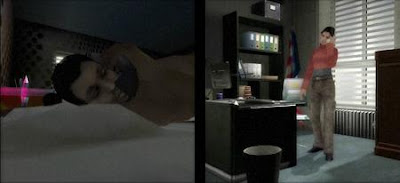

Changing focus now, the aspects that were heavily marketed are a letdown as well. As nice as it is to finally have inclusions such as damage and weather, it’s beside the point if they’re not executed well or come across as if their implementation was rushed. Strangely, damage doesn’t even exist until you’ve reached a certain level (40, to be precise) in the game meaning that only the dedicated are going to get to experience the addition, despite the incessant requests for it to be included over the years. Casual players and those who just want to drive some exquisite cars around some lovely locations won’t get to see the damage modeling the way it was intended -- where bumpers and the like can come off -- and instead will only get to see the unrealistic (and, it has to be said, jarring given the otherwise impressive visuals) bounces and bumps -- with no visible affect to the presentation of the car -- that the Gran Turismo series is synonymous with. They might, if they’re lucky, start to see some scrapes and scratches if they make it past level 10 or so but, like the entirety of the damage model anyway, it will remain cosmetic at best and doesn’t change the experience of playing the game. Speaking of which, this superficial damage -- one of the biggest touted features in the lead up to the game’s release -- isn’t even the best we’ve seen in the genre, once again disappointing anyone who expected it to live up to its predecessors’ prestige. Weather and night racing were the other big elements celebrated before launch, the suggestion being that they were new to the series and included to satisfy those wanting them ever since Gran Turismo 4. They’re not new, however, with night racing existing in every single installment since the original game in the Super Special Stage courses, and wet roads (read: no dynamic weather, that is new) also appearing along the way as well. What this means is that the former is false advertising -- though admittedly, racing as day transitions to night is new and absolutely stunning too -- in terms of how its implementation was implied, and the latter already catered to the difference wet driving can have on the gameplay experience, people (and seemingly Sony too) have just appeared to have forgotten about it. So that makes both features not new, then, though to their credit they are what they should have been from the get-go, alleviating some of the issues that this attempt at marketing arose. That doesn’t make them perfect, however, with night’s appearance looking blurry at times -- particularly while watching replays -- and rainfall being 2D like the trees, not to mention inconsistent (in terms of density) with what you see fall on the windscreen in the in-car view, or the water spray from the tires as a vehicle passes. It’s minor and, personally, I’d much prefer the idea that these additions were finally implemented than for them to be perfect, but it’s worth mentioning anyway, especially considering Sony and Polyphony’s strong focus on trying to be at the forefront of fidelity and innovation. Other games have done it better but they don’t want you to realise it.

Changing focus now, the aspects that were heavily marketed are a letdown as well. As nice as it is to finally have inclusions such as damage and weather, it’s beside the point if they’re not executed well or come across as if their implementation was rushed. Strangely, damage doesn’t even exist until you’ve reached a certain level (40, to be precise) in the game meaning that only the dedicated are going to get to experience the addition, despite the incessant requests for it to be included over the years. Casual players and those who just want to drive some exquisite cars around some lovely locations won’t get to see the damage modeling the way it was intended -- where bumpers and the like can come off -- and instead will only get to see the unrealistic (and, it has to be said, jarring given the otherwise impressive visuals) bounces and bumps -- with no visible affect to the presentation of the car -- that the Gran Turismo series is synonymous with. They might, if they’re lucky, start to see some scrapes and scratches if they make it past level 10 or so but, like the entirety of the damage model anyway, it will remain cosmetic at best and doesn’t change the experience of playing the game. Speaking of which, this superficial damage -- one of the biggest touted features in the lead up to the game’s release -- isn’t even the best we’ve seen in the genre, once again disappointing anyone who expected it to live up to its predecessors’ prestige. Weather and night racing were the other big elements celebrated before launch, the suggestion being that they were new to the series and included to satisfy those wanting them ever since Gran Turismo 4. They’re not new, however, with night racing existing in every single installment since the original game in the Super Special Stage courses, and wet roads (read: no dynamic weather, that is new) also appearing along the way as well. What this means is that the former is false advertising -- though admittedly, racing as day transitions to night is new and absolutely stunning too -- in terms of how its implementation was implied, and the latter already catered to the difference wet driving can have on the gameplay experience, people (and seemingly Sony too) have just appeared to have forgotten about it. So that makes both features not new, then, though to their credit they are what they should have been from the get-go, alleviating some of the issues that this attempt at marketing arose. That doesn’t make them perfect, however, with night’s appearance looking blurry at times -- particularly while watching replays -- and rainfall being 2D like the trees, not to mention inconsistent (in terms of density) with what you see fall on the windscreen in the in-car view, or the water spray from the tires as a vehicle passes. It’s minor and, personally, I’d much prefer the idea that these additions were finally implemented than for them to be perfect, but it’s worth mentioning anyway, especially considering Sony and Polyphony’s strong focus on trying to be at the forefront of fidelity and innovation. Other games have done it better but they don’t want you to realise it.Beyond that, elements of the game’s handling physics (which I will explore in a future post); the omission of classic tracks such as El Capitan, Seattle and New York; and archaic problems such as invisible walls (particularly on the Top Gear track) make for a confusing product, one that is so inherently amazing whilst, at the same time, a disappointing and lackluster experience. Gran Turismo 5 is undoubtedly the best game in the series but its flaws are bizarre, its handful of last generation (or worse, beyond) design choices are baffling, and, overall, as a product released in 2010, it’s a game that’s not only a letdown, it’s an inexplicable disappointment.

Why that is remains to be seen; why the game is so good is something I’ll reveal in the next post of this series.

*To be fair, Gran Turismo 5 isn’t the only game to feature 2D ‘paper’ trees. They can be found in its main competitor Forza 3, as well as in games such as Alan Wake. No matter which game they exist in, I always shudder when I find them as it certainly breaks the immersion during play.