It’s very easy to forget some things when discussing a game as intriguing and, in my opinion, important as Fahrenheit. With so many different and valid points of discussion, remembering absolutely everything you wanted to speak about is pretty much impossible, regardless of whether you take down notes or not. This happened to me during my conversation with Michelle, so now that I’ve remembered what I neglected to include in that discourse, I’m posting my leftover thoughts here.

It’s very easy to forget some things when discussing a game as intriguing and, in my opinion, important as Fahrenheit. With so many different and valid points of discussion, remembering absolutely everything you wanted to speak about is pretty much impossible, regardless of whether you take down notes or not. This happened to me during my conversation with Michelle, so now that I’ve remembered what I neglected to include in that discourse, I’m posting my leftover thoughts here.Antagonist Confusion

A sticking point for me personally was the confusion the game demonstrated when it came to having an antagonist. Uncertain as to whether it wanted to be a game or a movie, it constantly swapped between requiring one -- as a game -- and not needing one, something blatantly obvious while conducting my second playthrough. When the game begins, there isn’t really any antagonist -- sure, it’s vague as to why Lucas has performed the murder in the diner and it could very well be the result of an antagonist’s doing, but the focus of the game keeps its eye firmly on character development, meaning we don’t need to know about nor care for an antagonist while we learn who Lucas, his brother Marcus, and the two detectives, Tyler and Carla, are. It’s only at the midpoint of the game that we start having to deal with an antagonist -- something that quickly exacerbates into multiple, confusing enemies. It’s also at this point, intriguingly enough, where the game starts to lose its way, delivering crucial narrative information (such as what the ‘Indigo’ in Indigo Prophecy means) at a far too overwhelming and abrupt pace, confusing the player’s comprehension of the events taking place due to its erratic nature. So, in some respects, you could divide the game into two separate parts: the “film” section -- the first half of the game -- where we learn who the characters are, what their personalities and interests are like, how they start to connect to the overall narrative and, indeed, each other, plus anything else that fits together nicely when it comes to conveying the game’s story and providing its exposition; then the “game” section (second half) where the Quick Time Events are used more frequently, at more intense speeds due to the haste the story (thinks it) needs to move along at, explanations and justifications (for your actions) are attempted and the introductions of the various antagonists are seen. This split personality, if you will, really hinders the overall experience and absolutely breaks the game’s pacing, the confusion residing in the why: why does it need to suddenly deal with intensity and epic action sequences, when part of the appeal of the game in the first place was the intrigue, mystery and simplicity of the mundane actions and interactions in the beginning? Why bother introducing enemies when the four main characters are, in a way, opposing forces to begin with? Why did Quantic Dream feel the need to really chase after the supernatural elements when the game’s reality -- believable characters, realistic locations, menial activities -- was already fascinating to begin with? It’s just too destructive to what I saw as the intended experience, and it brings down an otherwise incredible game.

Music Match

Music MatchI was pleasantly surprised in both playthroughs -- my original one back when the game came out and the recent one for my discussion -- at the use of music in the game, particularly how subtle it was. The original score was a great accompanying feature that worked well to convey the different moods the characters were having, the atmosphere that surrounded them, and the emotion necessary to demonstrate to its audience that these characters, these people, were worth paying attention to and caring about. Back then I was used to scores that were designed for particular levels -- think Metroid Prime or Perfect Dark -- that, while excellently composed and catchy, didn’t pack the same kind of impact that Fahrenheit’s score does, or other narrative-focused games such as Metal Gear Solid or Final Fantasy. It was particularly nice at conveying the maturity that the game itself seemed to be trying to achieve, but I think it’s fair to say that the music was more successful than the overall game. Last but not least, the inclusion of four licensed tracks from rock band Theory of a Deadman was neat both for suiting the game’s themes and atmosphere, as well as featuring discreetly in the various characters’ apartments, providing a good background ambiance whilst performing the trivial tasks.

Love Matters

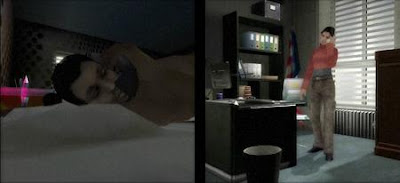

Love MattersI’ve always been interested in the game’s portrayal of sex -- particularly the sex scene in the third act and how it managed to largely fly under the radar while Grand Theft Auto continued to feel the repercussions from the “Hot Coffee” fiasco and, more recently, the mostly unnecessary controversy surrounding Mass Effect that was blown way out of proportion -- but more importantly, the game’s approach to conveying and expressing love was not only poignant, but significant, I feel, in moving the medium forward. By featuring that sex scene near the end of the game, nudity and all, Quantic Dream showed that they were not afraid to include anything that would enhance the story they were trying to tell, and that they didn’t care if it caused controversy or not. But, despite being happy with the inclusion of sex in a videogame finally -- why shouldn’t the medium be allowed to contain or portray it if it suits the context it exists in? -- it was the relationships between the characters that stood out the most. Scenes where you spend time with significant others, either by conversing with them, arguing with them, or expressing sorrow as you watch them collect their things from your apartment, went a long way into conveying the humanity that permeates these people and their lives, and it was really enjoyable to be able to experience that in a medium that was still very juvenile back then. Much like the game itself, it was unlike anything I had experienced before in a videogame, and reflecting on the love portrayed was very inspiring, creating a desire to see it occur more in the medium and a need for similar, compelling characters in the future games that I would play. With games like Heavy Rain, BioShock, The Darkness and even Portal existing these days, it’s nice to see that my wishes were and are being fulfilled to some extent, but we’ve still got a long way to go.

At the end of the day, and something I hope I communicated in my discussion with Michelle, Fahrenheit isn’t perfect and, with the benefit of hindsight (and a revisit), does deserve some of the criticism it receives, particularly regarding its third and final act. But for all the flaws and confusion, misdirection and incongruity, it still delivered an engaging story, had a cast of characters that I absolutely fell for, and gave me an experience that was utterly unique. For those reasons and so much more, it will remain in my memory as not just a game worth playing, worth experiencing, but a game worth considering: in terms of its maturity; its intention to be different and its desire to change the gaming landscape; and for trying to instill a sense of humanity in a medium that is anything but. I guess love really does matter, then.